What happens to retail when the lights go out?

Lights-out logistics and the future of supply chains

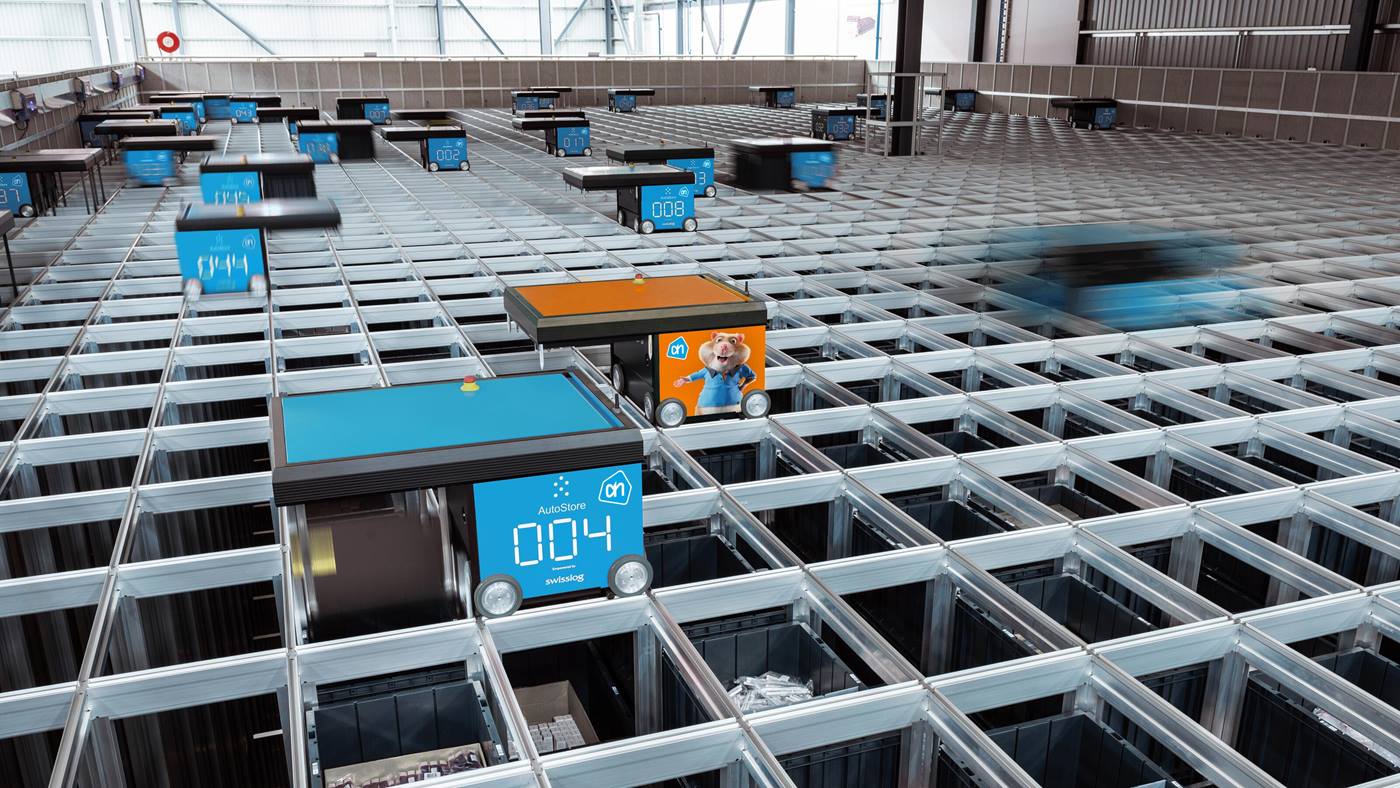

When we think of the ‘warehouse of the future’, we think of a warehouse full of product, but no staff driving back and forth on forklift trucks, no load handlers examining products and picking items onto pallets, not even an electric light – just sky high racking, shuttles, lifts, robots, conveyors and autonomous vehicles choosing their own paths through the darkness, self-navigating with laser guidance systems, detecting obstacles and moving silently past them. This is ‘lights-out logistics’, and although it may seem futuristic, it is already being used today. And lights-out logistics can help supply chains become more resilient in times of great uncertainty and disruption, such as financial crises and pandemics like COVID-19.COVID-19 and the Grocery Supply Chain

In February 2020, the World Health Organisation declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, and on April 1, 2020, the United Nations chief described it as “the greatest challenge the word had faced since WW2” with ripple effects spreading quickly through every part of industry. The same mega-trends that contributed to recent double-digit annual growth across the intralogistics automation industry have revealed themselves to be the most significant epidemiological factors driving the spread and impact of the COVID-19 viral pandemic.Typically, a company’s reasons for automation include increases in productivity, space efficiency, accuracy and the return on investment (ROI) these technologies bring, but there are also mega-trends at work in industry, such as globalisation, an aging population, health and safety, mobility, urbanisation, individualisation and digitisation, and these also place indirect pressure on organisations to automate. Megatrends and their effect on the supply chain during COVID-19. These megatrends have, in many ways, contributed to the rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, and have significantly impacted the supply chains of grocery stores and other essential suppliers. These impacts include:

Mobility – Within weeks of the world first learning about COVID-19, it was detected in multiple cities around the world, as businesspeople and tourists carried it with them on their travels. Air travel to and from the epicentre in Wuhan, China had increased tenfold since SARS1, resulting in a truly global pandemic within weeks. Within a few months, it had spread worldwide, borders were closed, airlines grounded, and the world economy was in deep crisis.

Globalisation – As governments searched for ways to build a virtual wall around their nations and states, the world economy entered a period of unexpected deglobalisation. Companies began questioning their over-reliance on imports, and looked to local suppliers to fill the gaps.

Aging Population – Early on, COVID-19 revealed itself to be a stronger threat to those over 70 years of age. And for those with underlying respiratory health conditions, it was life threatening. The high rate with which it spread within cities and the overwhelming number of elderly sufferers it placed into ICUs was of particular concern due to our aging societies. Panic buying, hoarding and a large increase in online orders forced major retail chains to re-think the way they supported their customers throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Health and Safety – Grocery stores, once places to do our weekly shop, were now understood to be critical infrastructure that would be kept open in any scenario, presenting a serious dilemma; how to protect the health and safety of frontline workers who could become exposed to the virus through interaction with seemingly well customers and vice versa. And what happens to a grocery chain Distribution Centre (DC) if a positive case is detected inside one of them? If the virus can survive on surfaces for a day or more, a DC worker could unwittingly become a vector for spreading the virus to new people, and new regions.

Urbanisation – An unfortunate by-product of urbanisation is that shoppers have a very limited appreciation for the current resilience of the grocery supply chain, which typically has months’ worth of inventory stored in warehouses and DCs. But what drives millions of urban consumers to panic buy in times of crisis, is initially a lack of preparation, followed by the fear of missing out – and like a run on the banks, this drives normally calm people to react in ways they normally wouldn’t.

Individualisation – In a modern world full of choice for the consumer, where even a can of tuna comes in 3 sizes and 10 types, and mass customisation is becoming the norm, one of the more startling symbols of the crisis was the decision by some grocery chains to make up ration boxes full of the same selection of essential items for the elderly and more at risk and sell them online. A great and necessary initiative, but one that stood in stark contrast to the existing megatrends.

Digitisation – One of the few weapons the modern world had against the disruption caused by a pandemic was undoubtedly the internet. And businesses, medical services and grocery chains alike made good use of it during the outbreak. Aside from the working from home practices many were newly getting accustomed to, doctors’ appointments were moved online, as were personal trainer sessions, social events, movie releases and for a rapidly increasing number of customers – grocery shopping, at least until online services became overbooked and needed to be targeted to just the most in need.

Utilising automation for productivity and resilience

As explained by the CEO of Americold in a BBC article in mid-April 2020, there has never really been a shortage of food during the outbreak, because, at any one time up to 3 months’ worth of goods have existed inside the supply chain. The challenge has been getting it out of supplier’s warehouses, into and out of the grocery supply chain National Distribution Centres (NDCs), Regional Distribution Centres (RDCs), and local DCs, and onto the stores shelves fast enough to keep up with demand.

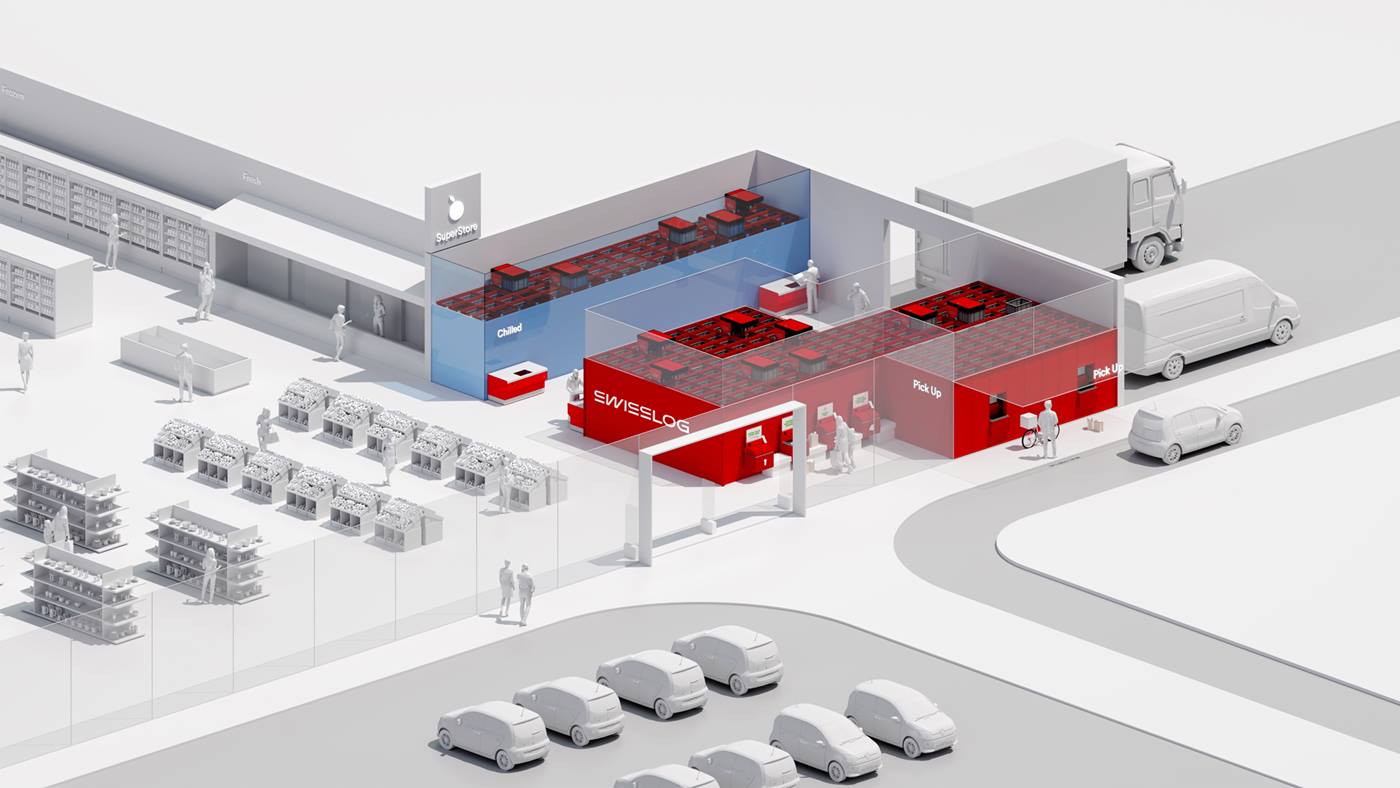

High density, high throughput Automated Storage and Retrieval Systems (ASRS) technology for pallet handling, such as Swisslog’s PowerStore, could be real game changer in these prolonged spike scenarios moving forward – providing much needed horsepower to grocery chains willing to shift their focus from just-in-time to just-in-case.

It has already been deployed inside the beverage supply chain, where a low number of very fast moving SKUs distributed at pallet level is the norm, but it could work just as well inside the grocery supply chain to look after the top 200 or so most in demand products.

A global supermarket giant has become one of the early adopters of Swisslog’s PowerStore system, which is currently in the testing phase in its distribution centre in the UK. To explore this concept in greater detail and read our Recommendations for board and managers download our latest Kaizen Paradox III 'A Case Study: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Effect on the Grocery Supply Chain.'

In the contemporary frozen food logistics sector, automation plays a pivotal role in enhancing efficiency and maintaining quality. Smart technologies and robotics are revolutionizing the cold chain, empowering food manufacturers and distributors to meet increasing demands. As these technologies become integral to operations, it's essential to maximize their potential for capacity and efficiency while maintaining the highest standards.